In the state of Sinaloa, families of the disappeared search for the bodies of their children in farmland and swampland, on beaches and in cemeteries. Bodies to name and return to their home.

Poverty has led to the trafficking and exploitation of thousands of people. While many disappear, others are sold by their families.

The nature that we usually deal with when it comes to disappearances is one that is found everywhere regardless of place, space or time. It’s human nature.

If we are to look at the many ways in which humanity has evolved, we have a lot to show for: technology, medicine, engineering, entertainment. However, it seems like there is one area where we have not made any progress. As much as we’ve tried to eradicate it, slavery is still up and running.

Humans are exploiting other humans for their own benefit and profit. Human nature hasn’t changed in that aspect: greed, lust and power are still very much the traits that control it.

In Romania, we have lost tens of thousands of people to the dream of a better life somewhere in Western Europe or beyond. Whether it was a job that seemed too good to be true, a lover turned exploiter or a family so burdened by debt that they accepted to trade financial freedom for one of their children, the end result looked the same: people vanished into exploitation.

All tragedies, like exploitation and abuse, have a way of becoming mundane, because we have come to normalize them. Somewhere, deep down, we expect it to happen to someone else.

What is left of these people? Mothers still look outside their windows to see if their toddlers, who now should be in their thirties, might show up. Empty village schools that used to be filled with children’s laughter and play now only display shattered windows and keep forgotten books in their drawers.

It remains one of the biggest mysteries – how people who vanish into thin air are still so visible.

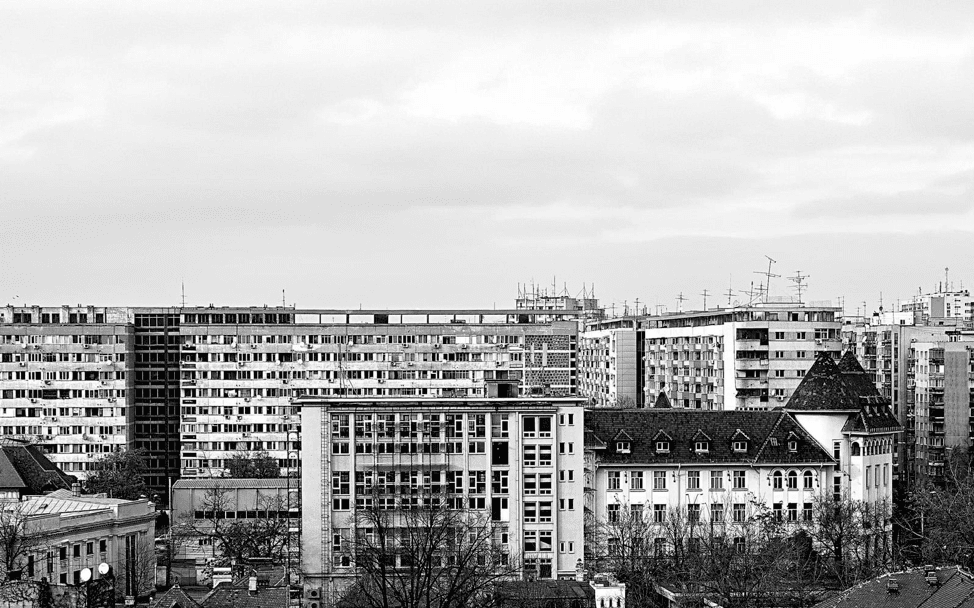

Bucharest, Romania. Thousands have disappeared in the country as a result of human trafficking and sexual exploitation.

Ioana Bauer works on the prevention and combatting of human trafficking and sexual exploitation in Romania. She has worked directly with survivors and advocates for better support for and identification of victims.

Carrying a bone is like carrying a newborn baby, because they’re delicate – little pieces that may be part of someone you are looking for, a newborn you don’t know. These little bones may still have DNA; they may give you someone’s identity… so fragile, so fragile that the only thing you can do is hold it gently so that it can be identified and have a name. Because a baby is the same, it doesn’t have an identity, it’s created by what you show it. A baby is life, and, just like life, it creates its own identity.

What is the body held in one’s arms? What takes shape when we rock the body of a child?

The body of a partner, of a brother, of a father, of a daughter, of a friend. What do we do when that body is lifeless and yet hold in our arms?

We’re so pleased when we see that there might be a body, it makes us very happy … but as we open the grave, when we discover the body, that’s when our strength gives out, our happiness fades, because seeing them there… some are handcuffed, their hands tied with cables, with rope, a 16-year-old girl was tied up and wrapped in a blanket, wrapped in a tarp and the tarp tied up with cables, she had her little gold jewellery, a little chain, her trainers, she was a little girl.

Those bones speak to us and transmit the willingness to be found. They don’t want to remain anonymous any longer, in that cold pit, where the last thing they felt was fear. I’m sure that my daughter, in the moment when she knew her life was in danger, cried ‘Mummy’… We’re here to take them back home.